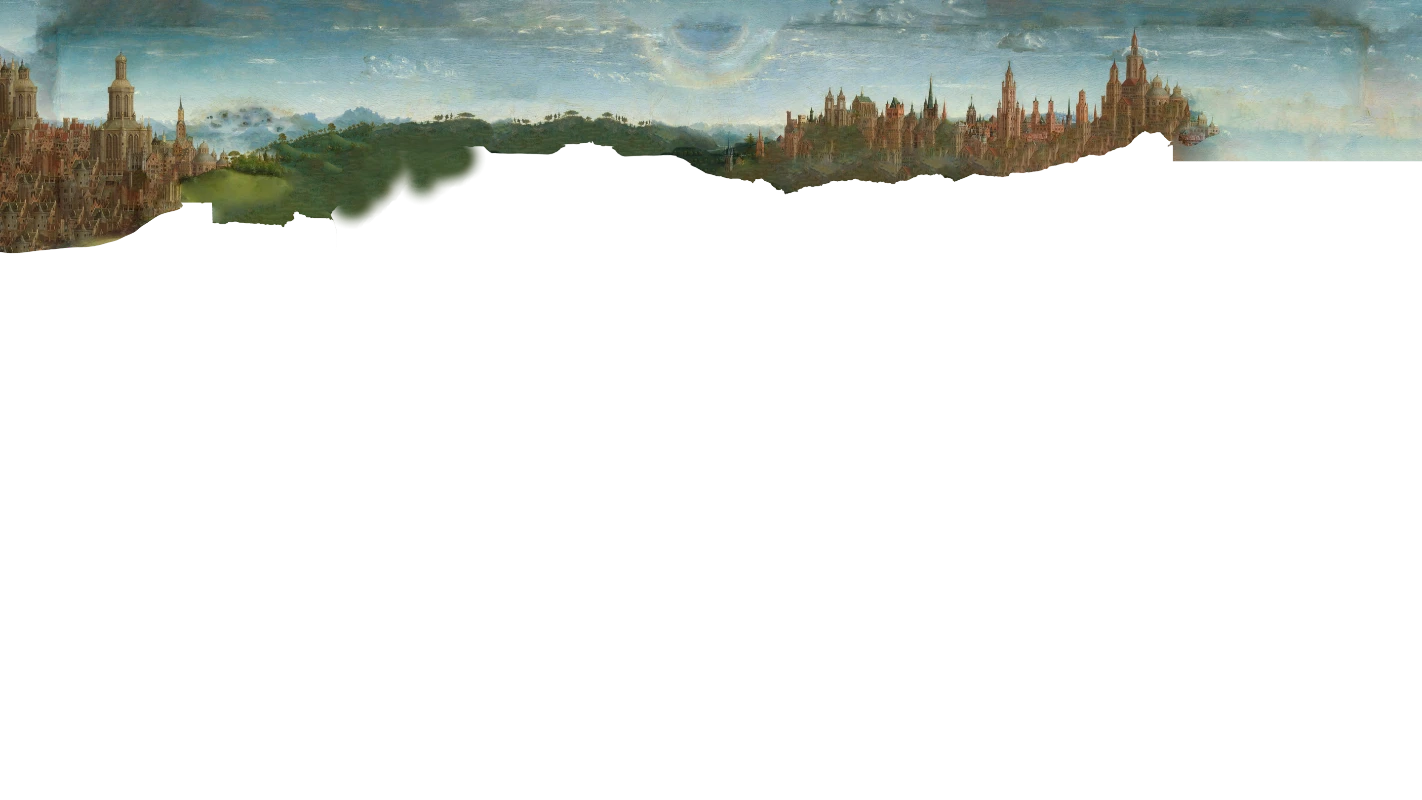

The Masses

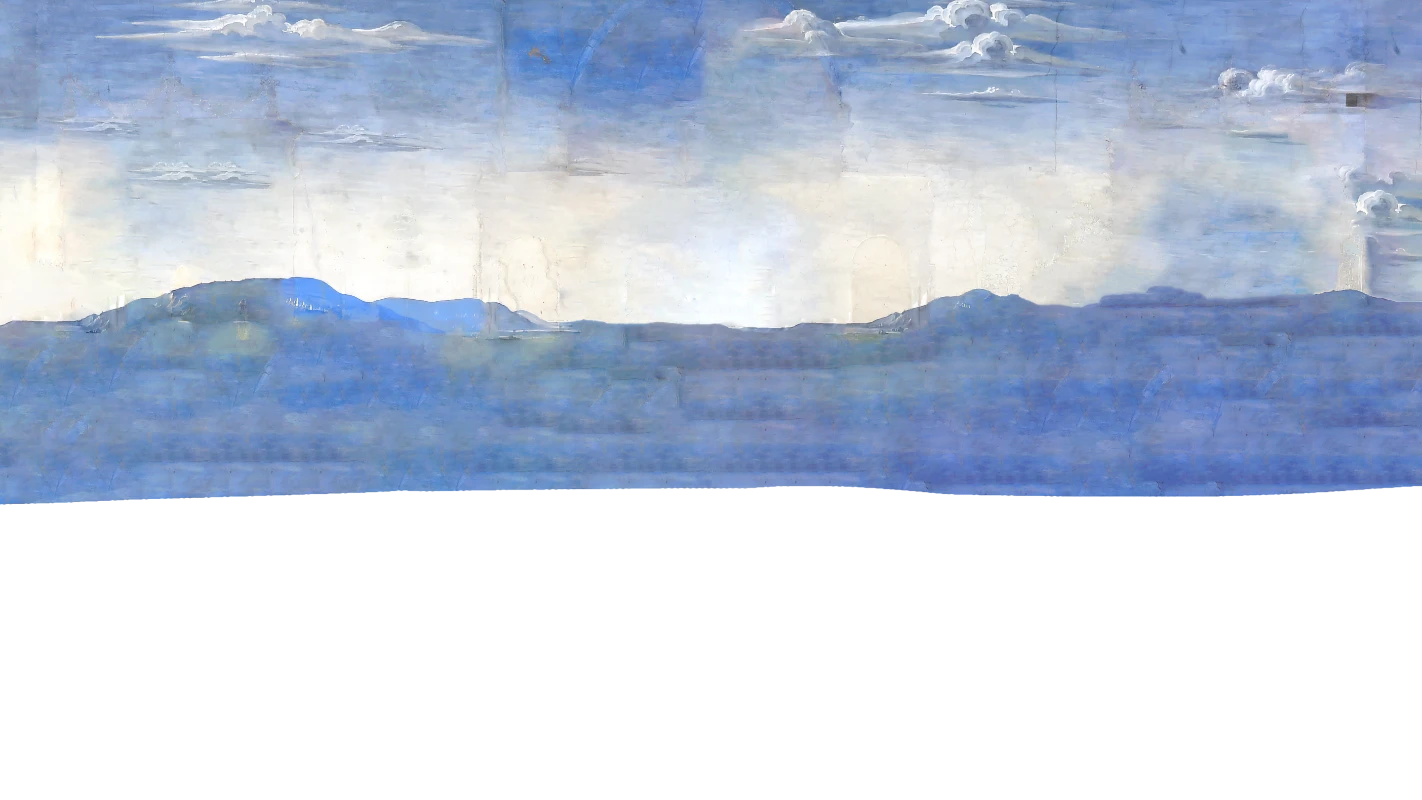

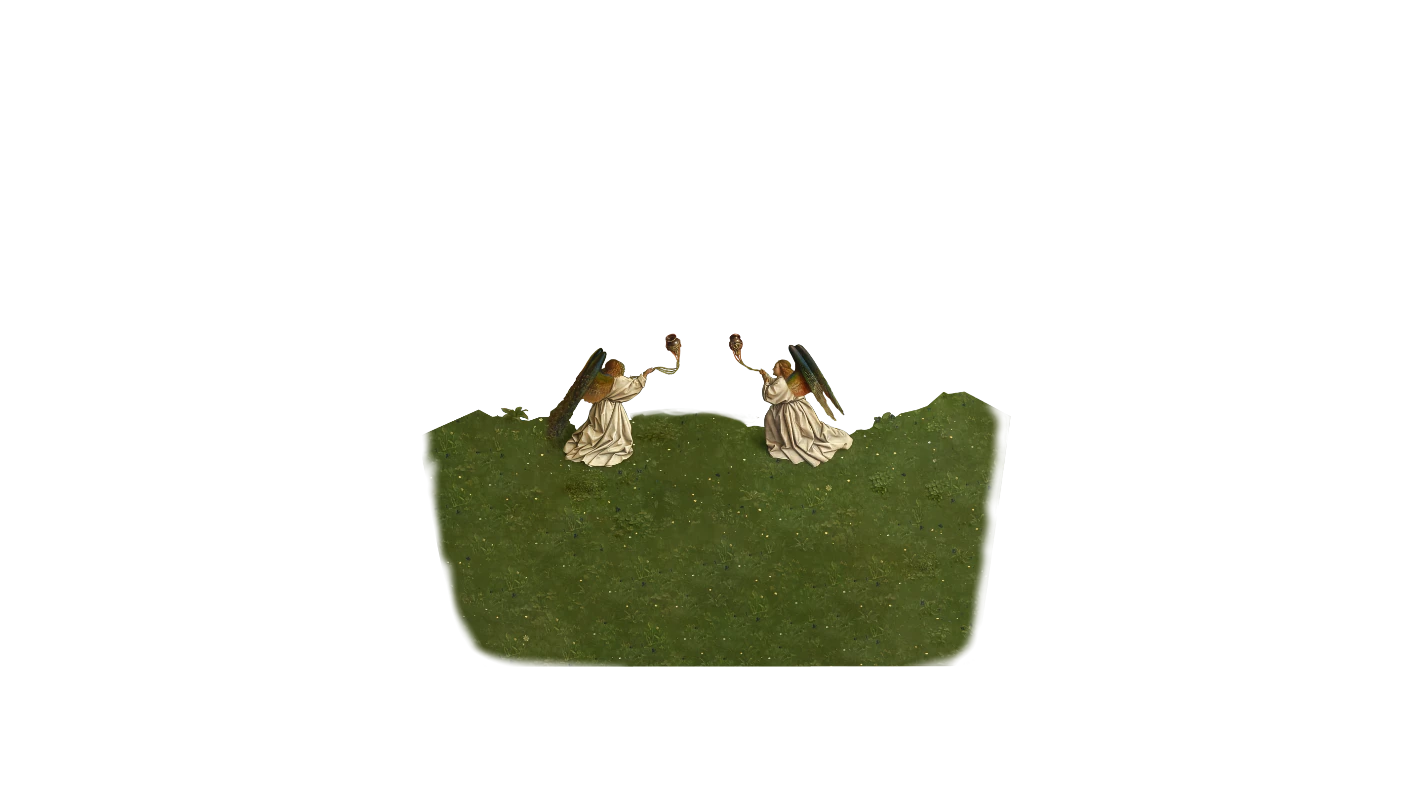

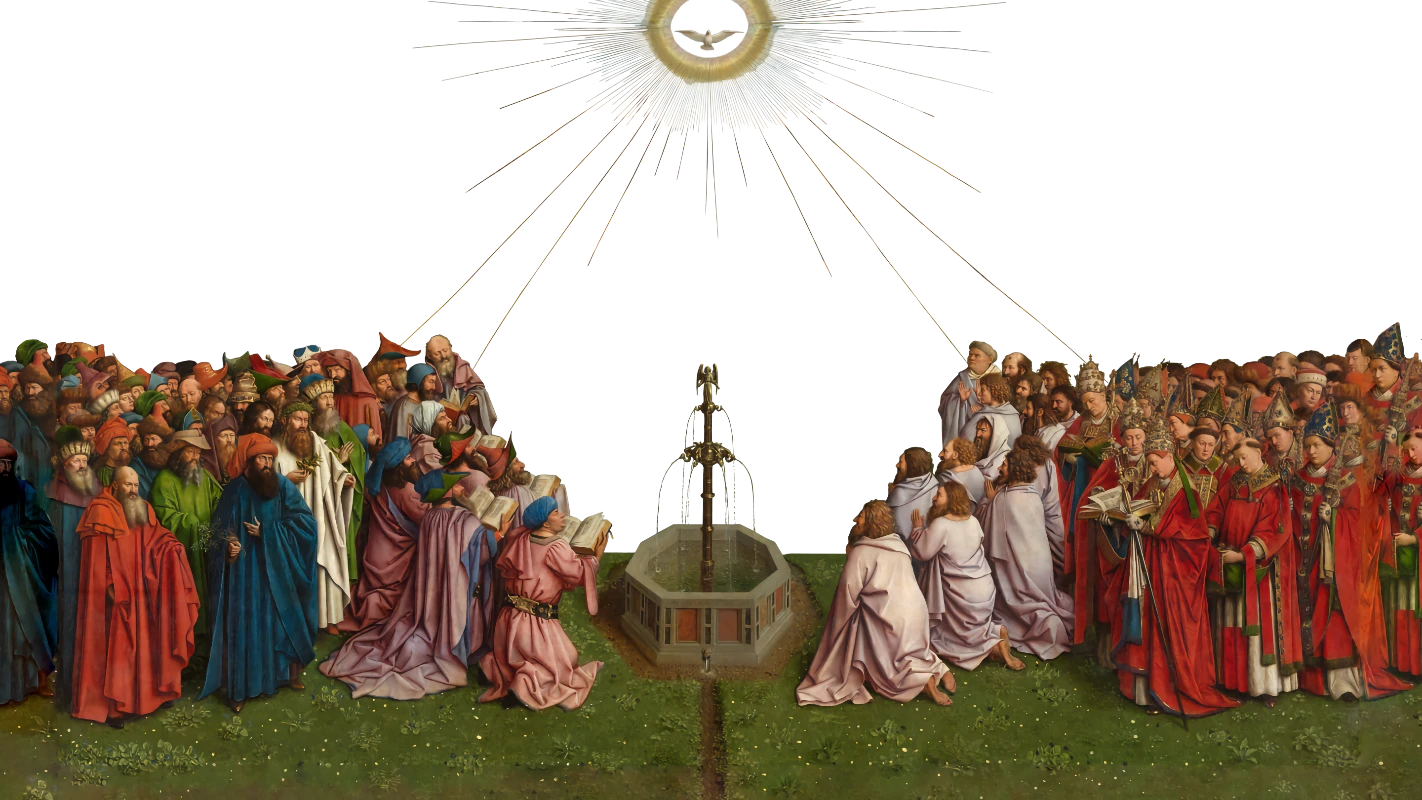

Jan van Eyck, The Ghent Altar (1432, detail) © artinflanders.be (photo: Hugo Maertens, Dominique Provost)

Josquin wrote 18 mass settings during his lifetime and created a unique compositional method and sound world for each of them. Discover the richness and diversity of the masses through The Tallis Scholars’ award-winning recordings and essays by their founder and artistic director, Peter Phillips.

Missa Une mousse de Biscaye

Probably one of the first mass settings Josquin ever wrote, Missa Une mousse de Biscaye perhaps shows the late-medieval origins of his musical language more clearly than any other of his masses.

Missa L’ami Baudichon

The early Missa L’ami Baudichon shows the young composer at the beginning of his career, exploring what he could do with the form.

Missa Ad fugam

Composing complex canons was a hallmark of excellence for every 15th-century composer. Josquin wrote two entirely canonic masses—Ad fugam, the earlier one, may be his most rigid and mathematically dense composition.

Missa Di dadi

Can a Renaissance mass be composed by the throw of dice? Missa Di dadi shows Josquin’s passion for mathematical shenanigans—and for gambling.

Missa D’ung aultre amer

Josquin’s shortest mass setting is based on a melody by his revered teacher Johannes Ockeghem and contains a moving musical tribute to the older composer.

Missa Gaudeamus

Missa Gaudeamus represents Renaissance artistry at its most intense. Based on a substantial chant melody, it deploys mathematics in a number of clever, but rewardingly audible ways.

Missa La sol fa re mi

True to its name, Missa La sol fa re mi is based entirely on the notes represented by these five solmization syllables on the medieval scale. By choosing a model so brief and versatile, Josquin opened up a completely new world of musical referencing.

Missa Hercules Dux Ferrariae

While he was working at the court of Ferrara, Italy, Josquin wrote an entire mass setting based on the name of his employer, Duke Ercole I.

Missa Faysant regretz

Building on the simplest four-note motif imaginable, Josquin creates some of his most densely argued and thrilling polyphony in the Missa Faysant regretz—a world of protean, swirling references and repetitions.

Missa Ave maris stella

Compact, smooth, concise—Missa Ave maris stella is the work of an assured and self-confident composer who has not only mastered the tools of his trade but redefines them for future generations.

Missa Fortuna desperata

The Wheel of Fortune is turning in Josquin’s mind-bending Missa Fortuna desperata, one of the first masses to be based on a polyphonic model rather than a simple melody.

Missa L’homme armé super voces musicales

Missa L’homme armé super voces musicales contains some of Josquin’s most complex compositional mathematics—a demonstration of his combinatorial prowess and a true miracle to his contemporaries.

Missa L’homme armé sexti toni

With its great variety of textures and easy-going yet sublime canons, Josquin’s second mass based on the popular “L’homme armé” melody feels like fantasia on the theme of the armed man, evoking minimalist sound worlds à la Philip Glass.

Missa Malheur me bat

In many of Josquin’s mass-settings the musical development culminates in the final movement—not unlike a Romantic symphony: the Agnus Dei of Missa Malheur me bat is a magnificent example and one of the greatest tours de force in the repertoire.

Missa Sine nomine

Josquin’s “nameless” mass is his second entirely canonic setting and shows the fruits of his experience in mathematical writing.

Missa De beata virgine

During his lifetime, this was the most frequently performed piece that Josquin had ever written—and it kept fascinating music scholars as far removed from Josquin’s time as the 18th century.

Missa Mater Patris

Missa Mater Patris exemplifies Josquin’s late-in-life, daring simplicity: gone is the dense polyphonic argument—instead we hear light, open textures delivered with a good deal of wit, even playfulness.

Missa Pange lingua

It is probably Josquin’s last mass setting—but it definitely is one of his best: the way Missa Pange lingua realizes a democratic conversation between all four voice parts had profound repercussions for later Renaissance music throughout Europe.